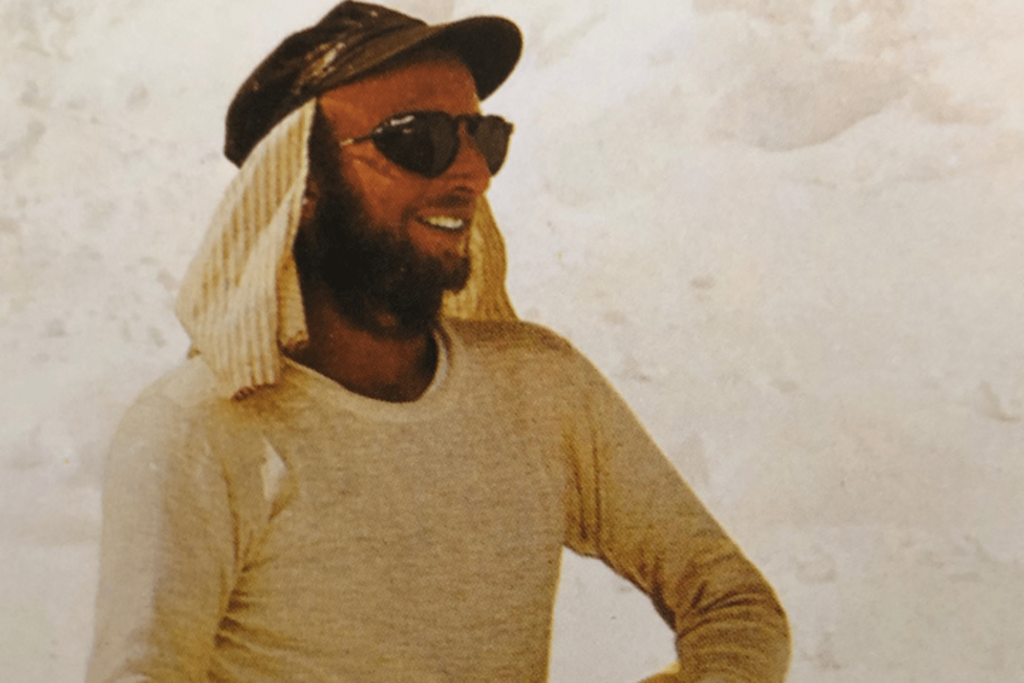

The American mountaineer Tom Hornbein died on Saturday, the 6th of May 2023 at the age of 92. He is the first who crossed the West Ridge of Everest with Willy Unsoeld in 1963. He left his name to the impressive corridor on the Tibetan side of the Himalayan giant. A look back at the life of an extraordinary mountaineer thanks to journalist Joel Connelly, who had the chance to talk to Hornbein on several occasions.

Tom Hornbein is known for one of mountaineering’s epic achievements: the 1963 climb of Mount Everest’s West Ridge with Willi Unsoeld (1926-1979), in which the two men traversed the 29,028-foot summit of the earth and spent a night exposed at 27,900 feet. He wrote a celebrated book, Everest: The West Ridge, reissued in 2013 to mark the 50th anniversary of the climb. But Hornbein never returned to the Khumbu region of Nepal,