From 9 to 13 June, Chamonix Mont-Blanc hosted its first mountain film festival, and we saw many of you there ! Such a festival was a natural choice for the “world capital of mountaineering”, which has attracted film-makers for over a century and provided backdrops for films of all types, from documentaries to Hollywood blockbusters. Bernard Germain, author of Dico Vertigo, Dictionnaire de la Montagne au Cinéma en 500 Films, looks back at Chamonix’s cinematic pedigree.

Gaston Refuffat always aimed high, so it is no surprise that he should ask Robert Redford, one of the 1980s’ biggest film stars, to play Jacques Balmat in a fictionalised account of Balmat and Paccard’s first ascent of Mont Blanc. Gaston saw the film as a sort of western, a tale of merciless rivalry between Geneva intellectuals, English aristocrats and Chamonix folk. It would end with Balmat heading into the mountains once more, this time in search of a seam of gold, never to return. Redford had agreed in principle, but it remained to be seen whether the American production’s insurers would cover the star on the slopes of Mont Blanc. This is an constant issue for risk-averse producers, who worry about raging torrents landing them in the soup or mountain storms burning their fingers. Show them a script that requires filming at altitude and they immediately start staring at their shoes.

Mountains are scary places and filming at altitude terrifies filmmakers. How many days will be lost to bad weather ? How much will have to be spent on safety ? Where will the stars stay ? What about clothing, food ? What about reviewing rushes or the difficulty of reshooting scenes with light that changes constantly as the sun peeks in and out between the summits ?

But even though capturing the magic of the mountains is a nightmare for producers, Chamonix, its valley and Mont Blanc have provided backdrops for dozens of films. So who were the eccentrics, the oddballs, the fanatics who put Chamonix on the film-maker’s map ?

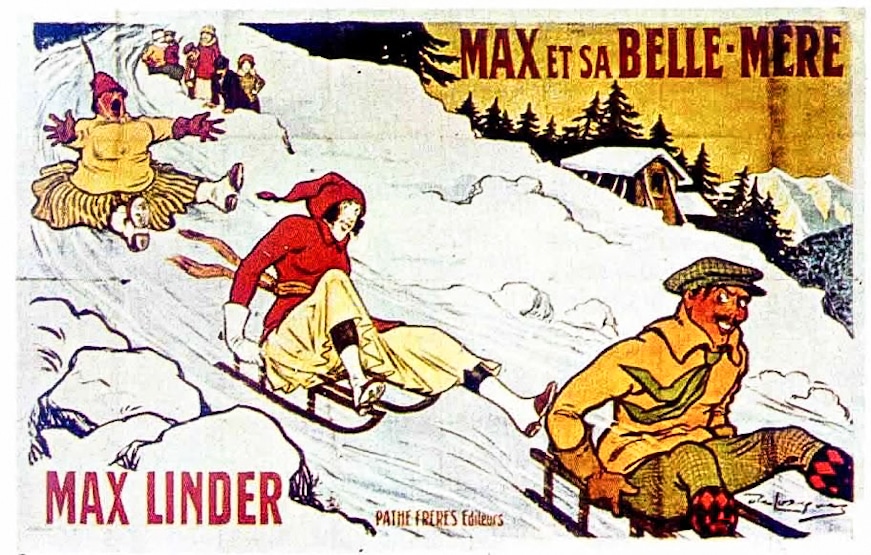

Chamonix owes its cinematographic debut to the brilliant comic actor, improvisor and director Max Linder, who first breezed into the Majestic Hotel during the winter of 1910. He was there to shoot (using two cameras – a novelty at the time) two short comedies whose snowy antics would inspire Chaplin when he made The Gold Rush. Linder’s joyously playful portrayal of skiing, sledging and skating in Max and His Mother-In-Law, the story of a honeymoon “à trois” with a very unwelcome mother-in-law, turned Chamonix, overnight, into a fashionable destination for Parisian society.

World War 1 had been over for less than two years when another eccentric team arrived in the valley. Abel Gance and his assistant, Blaise Cendrars, were two bulldozers, literally as well as figuratively : no sooner had they set up at the Col de Voza than they tore down the old tram station and uprooted all the pylons… cleansing the landscape to create a more pristine image. To shoot The Wheel, a railway melodrama that took its protagonists from Nice to the Mont Blanc tramway, the team climbed as high as the Petit Plateau, below the “Roof of Europe”, braved avalanches and hid from storms in the Grands Mulets Hut. Gance’s initial cut of The Wheel, released in 1922, ran for 9 hours, a true marathon! Blinkered critics praised it to the skies; free thinkers (including Robert Desnos) hated it. A restored version was edited down to 4 hours 22 minutes, elevated by Arthur Honegger’s original score.

Fast forward ten years, to 1930, and Chamonix becomes the stage for “Bergfilm’s” guiding lights, led by Arnold Fanck, with Luis Trenker as acolyte, and Leni Riefensthal as muse. The intrepid Leni played a champion skier and mountaineer who was trying to save a handsome meteorologist, freezing to death in the Vallot Hut. For Storm Over Mont Blanc, she made several climbs to the Vallot Hut, each time braving the crevasses surrounding the Grands Mulets. Most importantly, the long weeks of shooting taught her how to make documentaries; skills she would later use to serve the Nazis’ ignominious ideology, producing powerful propaganda films for Hitler and Goebbels (Triumph of the Will, Olympia). Through the crew’s physical and mental commitment, the film’s thrilling rescue scenes – by plane, on skis, on foot – and its captivating use of cross-cutting, Storm Over Mont Blanc pioneered the search for the spectacular, now achieved, often vacuously and boringly, using drones.

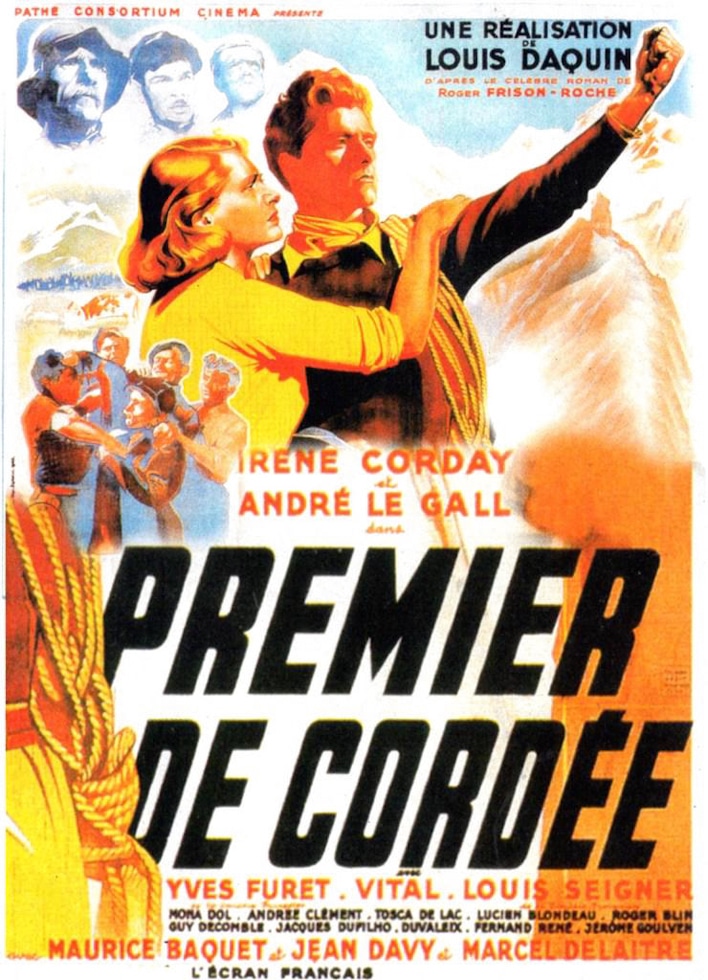

Daquin shot Premier de Cordée in 1943 with a strong team from Paris and Chamonix, one of whose motivations was to avoid being sent to Germany as forced labour

Just prior to and during World War 2, Chamonix was the scene of several more-run-of-the-mill French films, including Christian-Jaque’s They Met On Skis and The Killing of Santa Claus, Christian Chamborant’s Patrouille Blanche and Louis Daquin’s adaptation of Frison Roche’s best-seller Premier de Cordée (published in English as First on the Rope). Daquin shot Premier de Cordée in 1943 with a strong team from Paris and Chamonix, one of whose motivations was to avoid being sent to Germany as forced labour.

By the end of the war, producers had come to see Chamonix and the Mont Blanc Range as the most attractive and most reassuring venue for making mountain films. Production companies now knew that Chamonix offered several high quality hotels (the Majestic had become legendary), mountain huts that were almost comfortable, permanent rescue and helicopter services, and a large number of professionals (mountain guides, cameramen, sound recordists, etc.) who were used to working in dangerous places and ready to act as stand ins or extras.

The List

Chamonix’s pool of highly skilled technicians has grown continuously over the years (from the Tairraz dynasty to René Vernadet, from Jean Afanassieff to Gilles Chappaz, from Bernard Prud’homme to Denis Ducroz, from Didier Lafond to Bertrand Delapierre, from François Damilano to Christophe Raylat, Mario Colonel, Thierry Donnard, David Autheman, etc.), as has its stock of talented people capable of acting out even the most far-fetched mountain scenario. Sam Beaugey, an extreme skier, alpinist, BASE jumper and director, and Julien Herry, an extreme snowboarder and actor, immediately come to mind, but they are just two among many : the person you need for a shoot undoubtedly lives in the valley ! These facilities would be nothing without exceptional scenery that corresponds to creators’ needs and visions. In fact, the Mont Blanc range has become all the world’s mountains, standing in for :

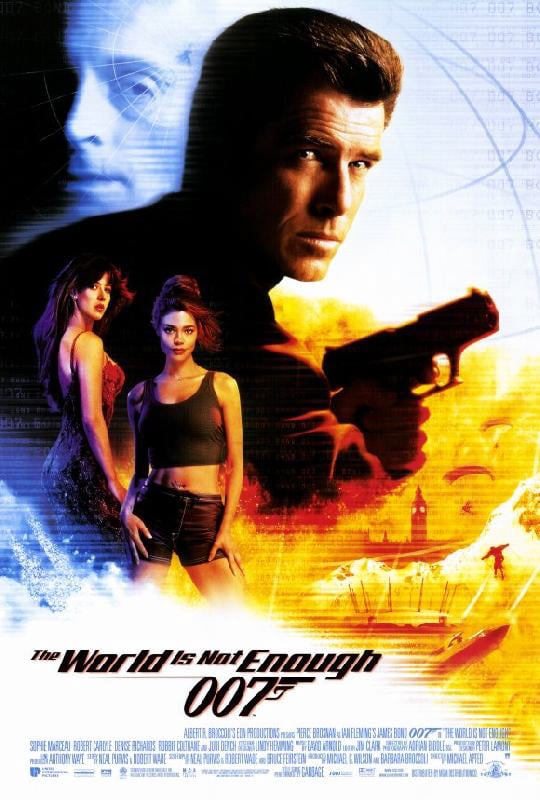

. The Caucasus, for James Bond, in The World Is Not Enough, by Michael Apted, with Sophie Marceau

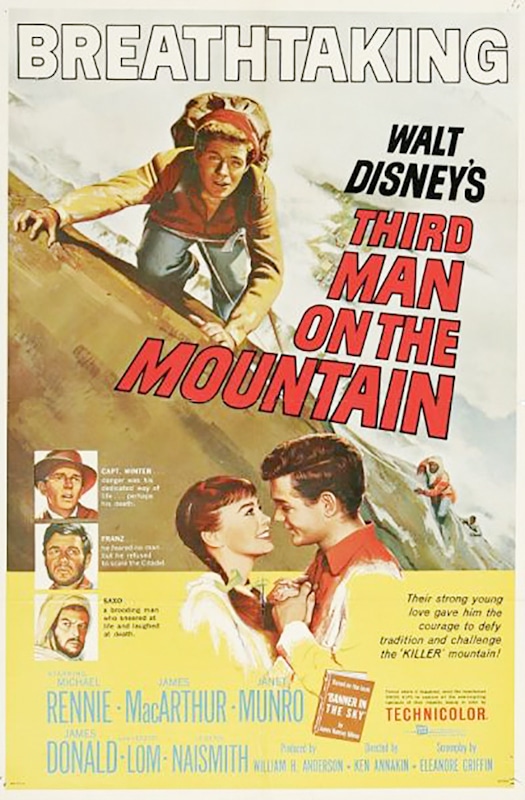

. The Matterhorn in Third Man on the Mountain, by Ken Annakin

. The Himalayas in The Man Who Would Be King, by John Huston, with Sean Connery, and in Up To His Ears, by Philippe de Broca, with Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Rochefort

. Everest in The Climb, by Ludovic Bernard, with Ahmed Sylla and Alice Belaïdi.

But the Mont-Blanc Range also played itself in :

. Starlight and Storm and Les Horizons Gagnés by Gaston Rebuffat, filmed by René Vernadet

. The Mountain, by Edward Dmytryck, with Spencer Tracy

. Malabar Princess, by Gilles Legrand

. Les Aiguilles Rouges, by Jean-François Davy

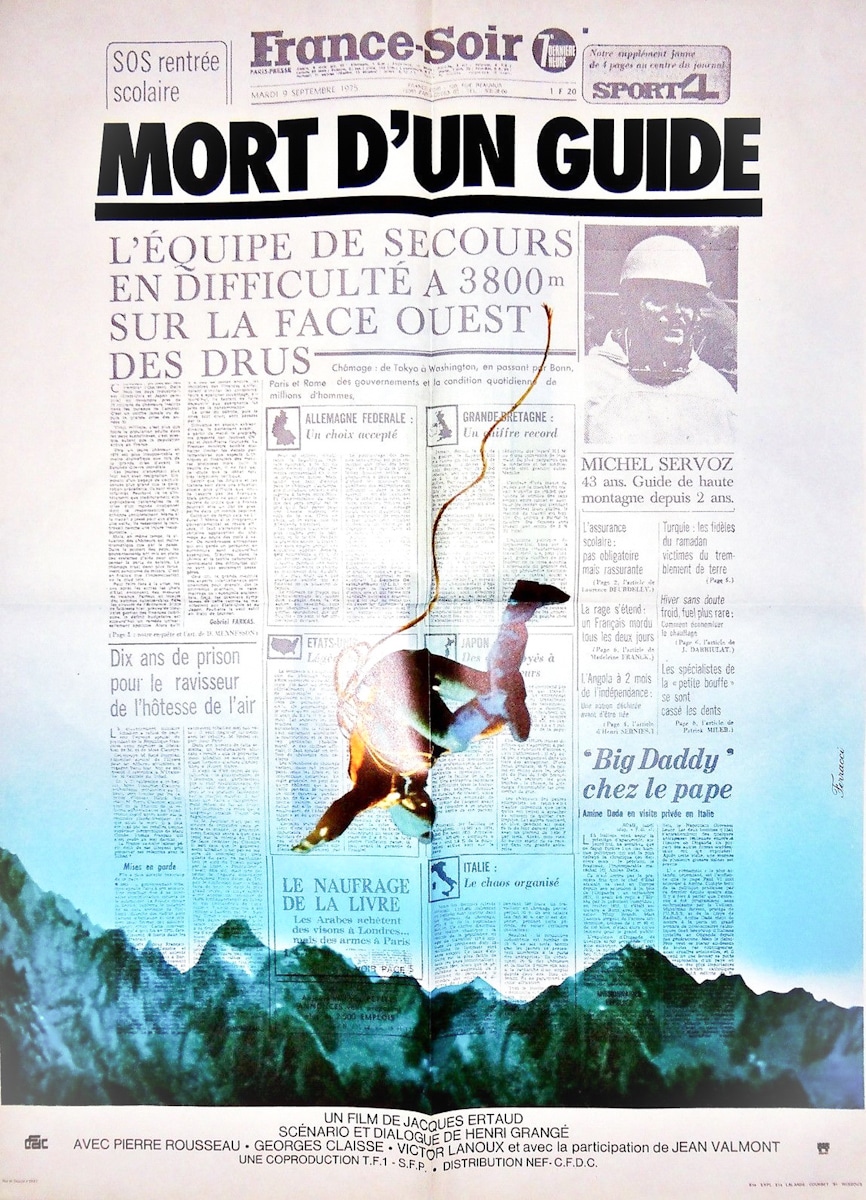

. La Mort d’un Guide, by Jacques Ertaud

. Les Etoiles de Midi, by Marcel Ichac, with Lionel Terray and René Desmaison

. Beyond the Summits, by Rémy Tezier, with Catherine Destivelle

. Christophe, by Nicolas Philibert with Christophe Profit

. Les Inconnus du Mont-Blanc, by Denis Ducroz

. La Face de l’Ogre, by Bernard Giraudeau

. Premier de Cordée, by Pierre Antoine Hiroz and Edouard Niermans

. Second Chance, with Catherine Deneuve, and Tout ça… pour ça, with Fabrice Luchini, both filmed by Claude Lelouch

. Les Marmottes, by Elie Chouraqui, with Marie Trintignant

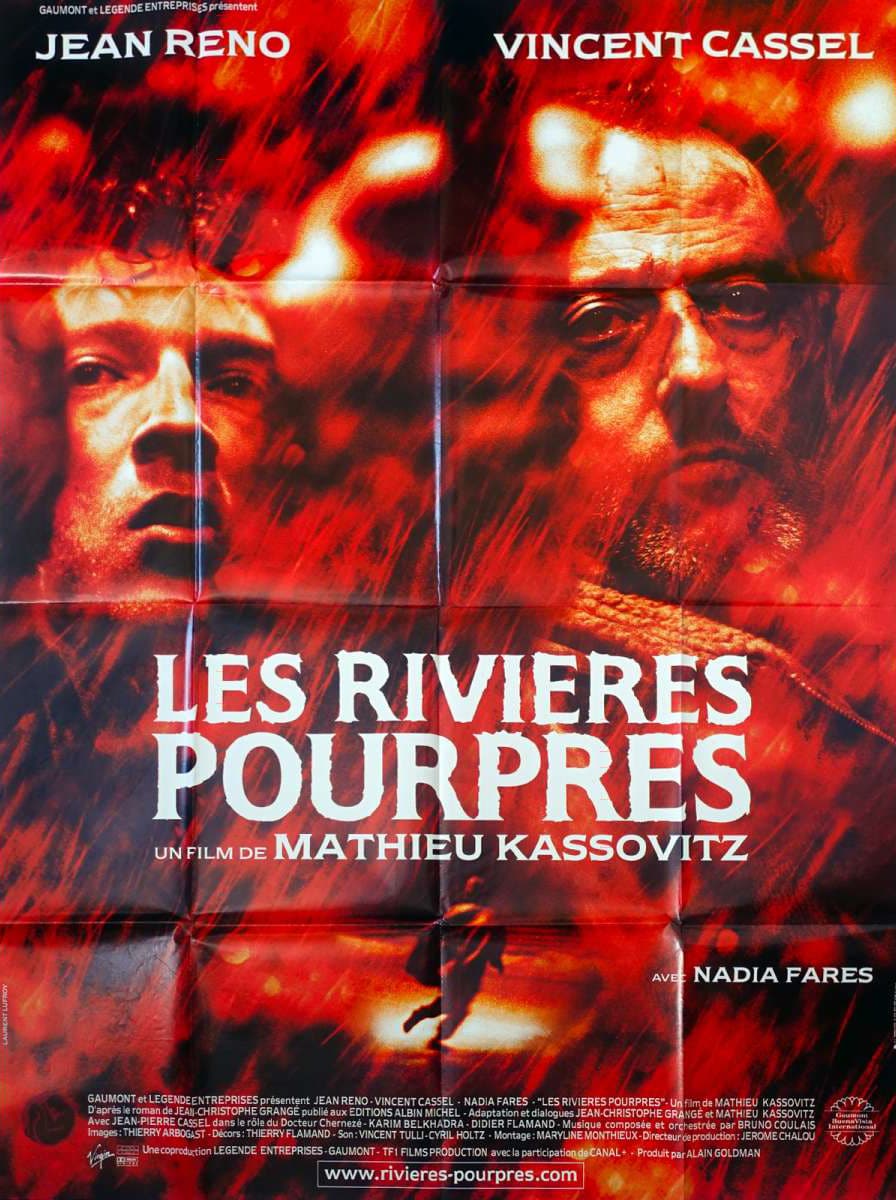

. The Crimson Rivers, by Mathieu Kassovitz, with Jean Reno and Vincent Cassel

. L’Amour est un Crime Parfait, by the Larrieu brothers, with Mathieu Amalric

. Tout là Haut, by Serge Hazanavicius

La Mort d’un Guide, in 1975, turned mountain guides into demi-gods for an entire generation of French people

It’s not unusual for a skier to begin a turn in the Vallée Blanche and to finish it in the Argentière Basin, or even the Caucasus !

The list is by no means comprehensive and gets longer every year. Two feature films are currently being shot in Chamonix : Les Têtes Givrées, by Stéphane Cazes, with Clovis Cornillac, and La Montagne, by Thomas Salvador, with Louise Bourgoin.

For filmgoers who know the Mont Blanc range, it is fun to play spot the difference while watching any of these films, as even the most famous of them are not safe from the editorial fixation with achieving a perfect cut, even at expense of geographical veracity. So, it’s not unusual for a climber’s foothold to be on one side of the valley and the corresponding handhold to be on the opposite side or for a skier to begin a turn in the Vallée Blanche and to finish it in the Argentière Basin, or even the Caucasus! And for no-one to notice… except you. Enjoy the films.