English legend Paul Ramsden and scottish climber Tim Miller climbed a new route on an unclimbed peak located few hours from Kathmandu, in Nepal. The Phantom Line (ED+) is a beautiful line on NW face of Jugal Spire, a mountain “found on Google Earth”. Here is the first part of their great story, told by Tim.

One thing that was certain on our trip to Nepal is that at some point in the afternoon there would be snow, usually hale, often thunder and lightning and frequently it would cloud over from 9am onwards, affording us only a couple hours of sun in the morning.

Every day for a month without fail we encountered an afternoon storm. So, when we were sat in our little tent in basecamp after completing our climb while the heavens showered down on the tent and thunder raged above, we couldn’t believe we had managed to snatch such a brilliant route from the improbable conditions.

Paul swore us to secrecy before he showed us

A few of his highly confidential new route ideas

It started 2 years previously when Paul Ramsden invited myself and Richard Kendrick to a Gritstone Club hut nestled under a cliff in the Lake District. There, Paul swore us to secrecy before he showed us a few of his highly confidential new route ideas on his laptop. We discussed them, then picked one and started to make plans for a trip. However not long after, COVID hit and scuppered plans for that autumn … and the following autumn as well.

The route we had planned was climbed in the meantime and Richard had to then drop out due to other commitments. By this point Paul and myself were frustrated at having our plans fall through so often despite all our rearranging efforts. We decided on a new objective and planned to go in spring as we didn’t want to wait another year.

Spring came around and we started to get organised. Thanks to Paul’s experience, the logistics for the trip were exceptionally straightforward on my part – a few zoom calls later and we were packed and ready to go. I got a train down to Paul’s house where we had a last-minute gear sort to make sure we weren’t missing anything and then we were driven down to Heathrow airport.

I first met Paul about 8 years previously when I had been climbing on Ben Nevis by myself one winters day. I was at the CIC hut getting ready to head down at the end of the day and there were two other climbers packing bags, so I asked them if they would be driving past Glasgow and could I get a lift. They were heading all the way to middle England, so they sped me back to Glasgow in double quick time, while Paul (who it was) told me stories of how he had once witnessed a murder while hitch hiking to the Alps when he was younger.

One of the lovely things about the world of climbing is how it is so small but welcoming. There are few sports where you can read about your heroes in books, the next day bump into them and a few years later be on a trip together.

We arrived in Kathmandu airport and after a slight panic of not finding our bags (another team had removed them from the conveyor belt) we were met by our tour agent with a ring of flowers to go round our necks (much appreciated given I didn’t smell great from the hours of traveling) and driven to our hotel.

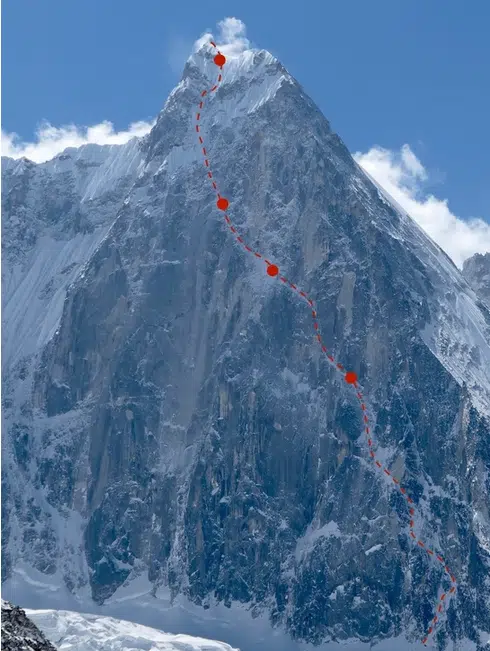

The Phantom Line, drawn by Paul with bivis marked. ©Paul Ramsden

We arrived in a small mountain village

surrounded by rice terraces and humid Jungle

The following day, Paul showed me around the sights of the city and we picked up our permit, gas canisters and other last-minute supplies. My impression of Kathmandu was not romantic or spiritual, as I had imagined, but of poverty and rundown buildings. We were introduced to our team of porters, then we all jumped in a bus and we were off out the city.

The roads got smaller, steeper, became single track, then turned to lumpy dirt tracks. Before long, the bus was miraculously bumping and swinging round hairpin bends on the edge of steep mountainsides. At the end of the road we arrived in the small mountain village of Bohtang, surrounded by rice terraces and humid jungle.

What’s interesting about the peak we were hoping to climb is that it had never seen a previous attempt or any interest at all despite being a 6-hour drive (and 4-day walk) from Kathmandu and it might even be the closest 6000m peak to the city. However, it’s secrecy may lie in the fact that it’s face is very hidden and the peak sits in front of the bigger peak Dorje Lakpa so that it doesn’t stand out on the skyline.

It was obvious on the first day of the approach that there was quite a divide in experience between the porters. From chatting to them, through broken English, we discovered that a few had never portered before in their lives and had previously worked as hotel clerks in Dubai, before COVID had brought an end to the tourism industry there and they had lost their jobs.

Now forced to take whatever work they could get, it must have been quite a contrast to their previous lives. They started to lag far behind the fit porters up front. The language barrier became an apparent problem when the porters at the front, who hadn’t understood where we wanted to stop for the night, carried on to the next stop forcing us all to continue.

A much shorter day took us

to a religious shrine by 5 mountain lakes

At that point we were introduced to the regular weather pattern with an afternoon thunderstorm. Tired and bedraggled the last porters arrived for the night 12 hours after setting off on what should have been a 2-day journey. We had gained 2000m of vertical ascent and we were concerned the porters, who were from Kathmandu and were not acclimatised, might suffer from the altitude.

The next morning, we were glad to find that everyone woke up well and able to continue. A much shorter day took us to a religious shrine by 5 mountain lakes. A nice place to stop for the day.

In this trip, we were travelling

“Ramsden class”

On previous expeditions that I have been on, to keep costs down, we have cooked for ourselves in our small tent at basecamp. These meals have often been pretty unappetising such as pasta and spice or rice and dried vegetables and I have gone home several kilo’s lighter. However, on this trip we were traveling “Ramsden class” and we had a Sirdar, cook and two cook’s helps. This resulted in luxuries such as warm bowls of water each morning to wash in, steamy mint-scented flannels to wipe our hands and face before each meal and an excellent 3 course meal 3 times a day at a table with table cloth and chairs!

Up to this point we had been walking on well constructed paths that allowed pilgrims and tourists to visit the lakes. However, these stopped and we were now on to rough tracks over passes and round mountainsides. It wasn’t until this point that a few of the porters decided to switch from their flip flops to trainers.

From the top of one of these passes we got our first view of the mountain we hoped to climb. White rugged peaks pierced the crisp blue skies, rocky ridges led steeply down to misty green valleys bellow.

Basecamp was situated in a valley of lateral moraine, quite muddy from the frequent rain and not a place we felt inspired to hang around for too long. So, we set off straight away, with light bags, on a reconnaissance mission.

The aim of which was to find a suitable path through the maze of the glacier that could lead us to our peak and also to try and get a view of the face, if we were lucky enough for it not to cloud over before we arrived. Traveling across highly crevassed and moraine covered glaciers is always an extremely slow and painful task. Paul pointed out that it was often at these points that injuries could happen and the most important thing for us to do now was stay fit and healthy.

As soon as he said this, I slipped on a wobbly boulder, fell back and put my hand out to catch myself. In doing so I bent my fingers back into an awkward position and tweaked some of the ligaments in one of the fingers. I didn’t want it to affect the expedition, but for the days after I struggled to hold a knife and fork and tie laces with that hand. I just hoped I would still be able to hang off an ice axe when the time came.

The face was made up of vertical granite,

with the exception of one scar of ice across it

The rest of that day we continued up the glacier, eventually climbing an embankment of moraine which brought us to a little alpine lake surrounded by grass and large boulders with views of the peak. It was an idyll spot. Having had our first view of the face we were blown away by the magnitude of it, looking at it side on we realised it was much steeper than we had thought.

The one photo we had seen of the face was from a Spanish team and looked at it straight on. We now realised the photo had been taken after a storm making it look very white leading us to believe there were lots of lower angle ice fields on the face. To the contrary, it was primarily made up of vertical granite, with the exception of one scar of ice across it. We couldn’t see yet if this ice linked up all the way.

Walking back down the glacier we knew we had discovered an incredible face, however there were several big question marks as to whether it was climbable. On the plus side we discovered a brilliant path that took us down a grassy moraine valley straight back to basecamp. Both aims for the day complete.

With fresh motivation, we launched straight into the acclimatisation phase the following day. With huge bags, packed with 7 days of food and all the kit we would want for the climb later, we set off up the moraine valley. We plodded along very slow under the weight of the bags and our unacclimatised lungs, eventually arriving at the “hanging garden” (what we had named the little alpine lake). We had hoped to lounge around, stretch and relax on the grass under the sun, but the weather had different plans and we found ourselves reading in the tent all afternoon while it snowed around us.

The next day, under an obvious boulder, we stashed all the kit that we knew we would need for the climb but wouldn’t want for the acclimatisation. Then we continued up a large flat glacier. The acclimatisation generally involved slogging for a few hours each morning to gain an extra 400m of elevation, here we would put the tent up and lie there for the next 18 hours. Mostly reading and sleeping and occasionally eating and getting up to pee.

We continued on until at 5700m and with splitting headaches we decided to stop and stay an extra night before descending. It was interesting that what had taken 5 days to get up took us a morning to get back down.

Still smiling despite the headaches. ©Tim Miller

Back at basecamp it was sinking in that what had required months of planning and weeks of in-country-preparation was now coming to a climax. We meticulously went through gear, cutting out anything that would add extra grams to our bags and triple counting out our rations.

Then, for 2 days it snowed and we were forced to rest in the tent reading books while the thought of the mountain hung over us. With apprehension building it was a funny thing to be tent bound while so ready to go.

Eventually a nice morning came along and off we went. The first stop was at the stash we had left under the boulder. We repacked and now with bags overflowing we continued gingerly up the glacier. Each of us struggling to amble over boulders while wondering how on earth we were going to climb a 1.5km face!

I sensed Paul had doubts

We set up camp for the night not far from our planned descent route. We left 2 meals and a handful of bars stashed under a rock for the likely scenario that we would be starving hungry and need a break when we got to this point after the route.

The next day saw us continue up the glacier and approach right beneath the face. It towered over us looking monstrously steep and imposing. We dumped our bags and walked up to the bergschrund.

All we could see was a sea of granite, our line of ice totally obscured from below. Paul seemed slightly subdued at this point and I can understand why. At the time I didn’t know what to make of such an impressive wall other than that I was in awe of it.

I went to sleep looking forward to giving it a go, but I sensed Paul had doubts over it being possible having seen the wall up close. Had all our weeks and months of preparation been for nothing? Had we bitten off more than we could chew?

> Read the second part of this story : Phantom line on Jugal Spire : a mountain exploration. The story 2/2.