With an unquenchable appetite for victory, the trail king has never been stronger. Now fathering two small children, managing a foundation and launching his own gear brand NNormal. How does he do it? Kilian Jornet himself tries to answer.

Once again, Kilian Jornet has had an extraordinary trail season, surely the best of his career, in a context where the competition has become much fiercer than when he first won races over 15 years ago. “He has never been this strong“, said Jean-Louis Bal, who was contacted by phone when Kilian’s victory in this year’s UTMB was on the horizon. “Before he went to Norway, he didn’t really train. He was just accumulating large volumes in the mountains and did his intensities on the races he multiplied throughout the season, especially in winter with the ski mountaineering world cups, which he stopped. Now that he has moved away geographically and limits his travel, he does fewer races but trains much better, especially in winter. And by doing fewer transfers to competitions, he trains as much or even more in volume, even with a family life“, continued the trainer based in Ugine (Savoie). He also coached the ski mountaineering champions Axelle Mollaret, William Bon Mardion, or the second of the UTMB 2021 Aurélien Dunand Pallaz. He knows Kilian very well for having advised him in his quest for a record at Sierre-Zinal in 2019, and for regularly discussing training issues with him.

Chatting with Jean-Louis Bal lifts the veil a bit on Jornet’s training, which is in many ways fantasized. The Catalan runner expatriated in Norway explains his approach on a site surely less consulted than his Instagram, Mtnath, which compiles among other things his thoughts on his training. Here are some of his reflections on his pantagruelic season.

(Re)motivation

Kilian has repeatedly stated that his challenge this year was to “was to perform well in short and long trail running races within a few weeks. For that I chose to participate at the 2 short races I believe are most competitive (Zegama and Sierre Zinal) and the 2 long ones that would offer the biggest competition this year (Hardrock 100 and UTMB). The schedule was also interesting because the races were alternated, so: short – long – short – long which didn’t really allow to make a bloc for short and then another for long but to do quick switches several times or be in shape for both distances at the same moment.”

This kind of sequence is surely a way for the Catalan to remotivate himself to do races that he has won multiple times. But this sequence is nothing new in his career. In comparison, his 2017 season with his Himalayan expedition and double Everest + Mont Blanc Marathon win + Hardrock win (with his arm in a sling) + Sierre Zinal win + 2nd at UTMB already looked like an absolutely incredible season. But maybe the performance slider was not pushed to the maximum for Kilian’s taste, and seeing all his records fall this year (except Sierre Zinal), this hypothesis seems good.

Father and athlete, how to

Simply be happy

You don’t do core? Neither does the best trail-runner in history.

Do not train too hard, in order to stay physically and mentally fresh

Kilian is a special case. When it comes to training,

it is his philosophy that should be remembered.

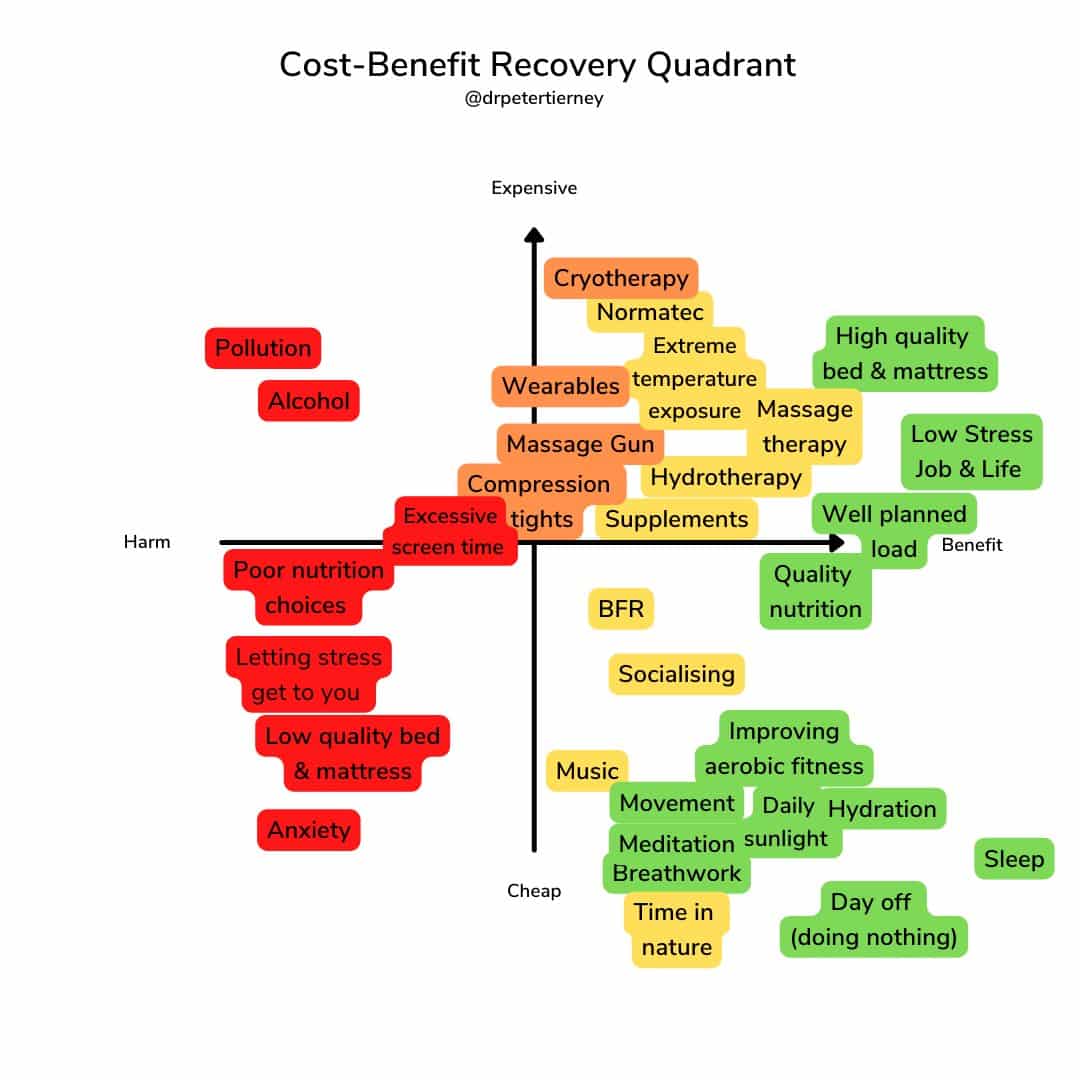

And Kilian is definitely a special case. It is rather his philosophy that we should remember. Know yourself (for example Kilian teaches us that he gets injured as soon as he does too much flat speed, it’s up to you to see what your weaknesses are), learn from competent people around you, adapt, stay on simple and cheap things (sleep, nutrition, evacuate stress) and don’t get lost in a technical training spiral.