On 21 June 1975, Jim Bridwell secured his place in El Capitan history when he and his companions climbed Yosemite’s biggest wall in a single day. Try to imagine: Harding had taken 47 days to ascend the 1,000 metres of the Nose in 1958 and 36 years would go by before Lynn Hill made the first one-day free ascent. In 1975, the Nose-In-A-Day was revolutionary. Bridwell, the feat’s architect, was an extraordinary all-round climber and mountaineer who would later make the first true ascent of the Compressor Route on Cerro Torre.

A climbing junkie, addicted to the world’s biggest walls: that’s not me speaking; it’s how Jim Bridwell describes himself in his short but superb autobiography, published by ICS Books. Bridwell died in 2018, less than a year after Alex Honnold had achieved the unthinkable by free-soloing El Capitan in just a few hours. (Freerider, the route he chose is hard but an easier free climb than the Nose.) André Gauci and Jacques Dupont made the first French ascent of The Nose in 1966 and by 1975 it had become a classic, albeit at such a high standard that even top climbers usually took at least three days to do it. Although climbers such as Charlie Porter had continued pushing standards on the most overhanging and smoothest parts of El Capitan, producing routes such as Zodiac (1972), Mescalito (1972) and Tangerine Trip (1973), El Cap’s most sought-after lines in 1975 were still The Salathé Wall and the Nose.

NIAD, Nose-In-A-Day

Under the full moon of 21 June 1975, Jim Bridwell, John Long and Bill Westbay did the short hike from the road to the majestic bastion of El Capitan. The Bird had driven back to Yosemite a few days earlier, foot to the floor of his battered Pontiac, trying to set a new record for the 45 kilometres from El Portal to the park entrance. Climbers at the time loved speed and despised helmets.

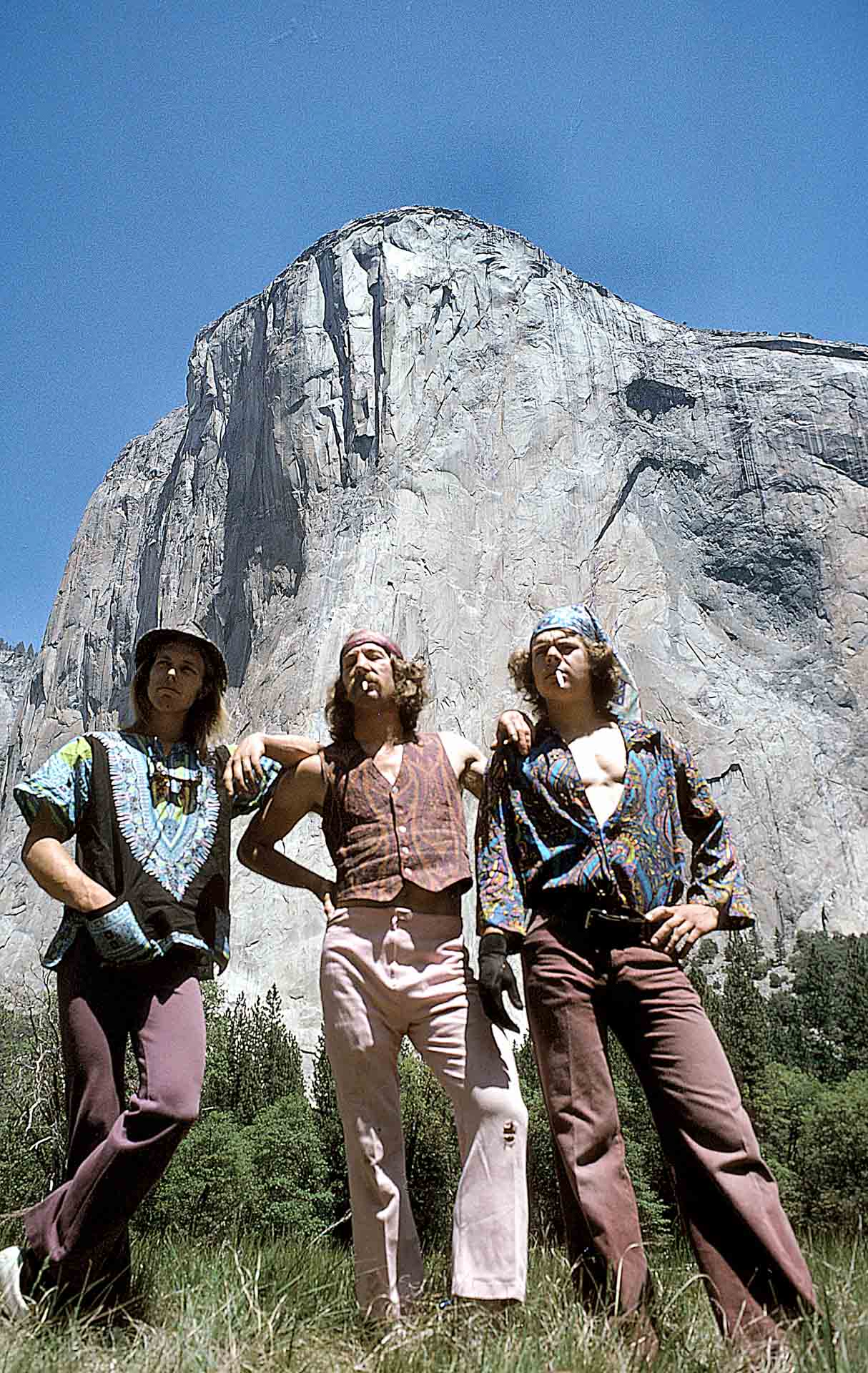

Bridwell and his companions ran up the first few pitches, having memorised every movement, every placement : “Pitches rolled by like dollars on a New York taxi meter. John flew up the Stoveleg Cracks with the certainty of the Yosemite veteran that he was. We reached the top of Dolt Tower by 6:15. Here, our clamor roused two bivouacked climbers from their slumber. Bleary-eyed, one of them asked where our haul bag was. I responded by pointing to a small rucksack on my back. His expression became more quizzical as he looked at our bizarre style of dress. In our purple and pink double-knit pants, worn with paisley and African print shirts, we presented a questionable apparition to any eyes— sleep-filled or otherwise.”

Pumping Out

Bridwell was fit, but he regretted not being in as good shape as John Long. By pitch 13, all three climbers’ arms were feeling the strain. Long started free climbing the pitch, pushing on high above his last runner, his arms totally pumped. As the Bird relates in his book: “In silent despair, he hung from a failing hand jam. With the last of his strength, he wedged a hexcentric nut into the crack, clipping into it just in time and averting an 80-foot airball.”

At 3 pm it was Bridwell’s turn to take the lead. Having worked for Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR), the way many climbers earned money in Yosemite, he was familiar with the corners of the final pitches, including the famous Great Roof. Thanks to the gear placed by struggling climbers and by rescue teams, the corners and belays were usually “festooned with fixed gear.” But Bridwell was out of luck: someone had removed most of the pegs a few days earlier. Long exhorted Bridwell to place the missing pegs as quickly and as far apart as possible, the key to speed in aid climbing :

– Hurry man, we gotta make it down before the bar closes.

In silent despair, John hung from a failing hand jam. With the last of his strength, he wedged a hexcentric nut into the crack, clipping into it just in time and averting an 80-foot airball. Jim Bridwell

The legendary photo of the Nose record breakers in front of El Cap, in 1975 ©Collection Bridwell

On 21 June 1975, the three weary climbers topped out on the summit of El Capitan after 17 hours 45 minutes of hard effort. It took another 11 years for the record to be brought down to 10 hours 5 minutes (Bachar and Croft). Then the 2000s saw the start of a frantic quest to reduce the record, which culminated in Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell’s sub-two-hour exploit in 2018. In 1975, before the advent of camming devices, Bridwell, Long and Westbay’s one-day ascent of the Nose was an exploit that opened new perspectives for the period’s leading climbers. And 45 years later, the average time for an ascent of the Nose is still… three days!

FURTHER READING: Jim Bridwell’s autobiography, Climbing Adventures : A Climber’s Passion (ICS Books)